11 December 2016

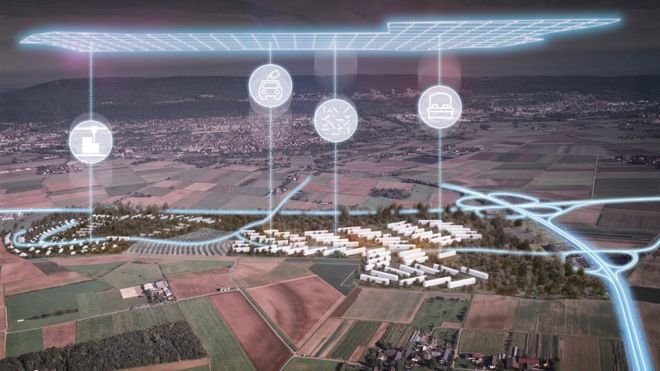

Aerial view of the village, (c) Carlo Ratti Associati

An abandoned military village in Germany could get a new lease of life as a hippy commune fit for the 21st Century

The vision, says Prof Carlo Ratti - who runs the design company Carlo Ratti Associati and heads up the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Senseable Cities lab - is to transform it into an "experiment for future living".

"We need to try out different things - that is important as architects and engineers - because it is how human society progresses," he tells BBC News.

"We started this project with a question, 'What would a commune based on digital sharing look like?' And an island of America in Europe seemed like a good test bed."

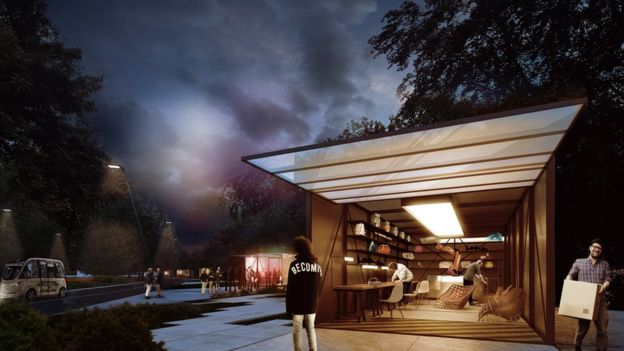

The commune will have small "fab labs", where things can be built, (c) Carlo Ratti Associati

If the vision becomes reality, residents will share accommodation and workspace and produce their own food and goods. It aims to accommodate 4,000 people in a 1-sq-km (0.4-sq-miles) site.

"It may resonate with a certain demographic, such as students and entrepreneurs, of which Heidelberg has many," says Prof Ratti. But it will be open to everyone, and potential residents are likely to be invited to submit their reasons for wanting to join online, with the community voting on who comes to stay.

At the heart of the commune will be the Maker Square, an area dedicated to digital fabrication. The maker movement is a trend for individuals and groups to create products from recycled electronics or other raw materials. Increasingly, it is making use of modern technology such as 3D printing to create cottage industries that can mass produce.

If the vision becomes reality, residents will share accommodation and workspace and produce their own food and goods. It aims to accommodate 4,000 people in a 1-sq-km (0.4-sq-miles) site.

"It may resonate with a certain demographic, such as students and entrepreneurs, of which Heidelberg has many," says Prof Ratti. But it will be open to everyone, and potential residents are likely to be invited to submit their reasons for wanting to join online, with the community voting on who comes to stay.

At the heart of the commune will be the Maker Square, an area dedicated to digital fabrication. The maker movement is a trend for individuals and groups to create products from recycled electronics or other raw materials. Increasingly, it is making use of modern technology such as 3D printing to create cottage industries that can mass produce.

There will be a maker palace for artists and musicians, (c) Carlo Ratti Asociati

For Prof Ratti, a communal way of life is not just more sustainable but more sociable. "If you live in a big city, you have access to lots of like-minded people, but in smaller communities you may only have a few thousand," he says.

"So why not create a like-minded community where it is easy to connect with people and sharing is the glue?"

His ideas were recently presented at German design exhibition Internationale Bauassstellung. IBA, the group that will ultimately decide what happens on the site, also heard proposals from other groups, including a car-sharing service to connect the site to Heidelberg using self-driving shuttles.

"It's about a process of transformation that we want to trigger," says Prof Kees Christiaanse, who works on the project. "Today, we are experiencing an atomisation of economic activity in ever smaller units that work complementary to large global firms. "Increasingly, we are depending on highly specialised small-scale enterprises.

"Carlo proposes a kind of infrastructure for these cross-fertilisations to take place, which will be of great value for developing the site."

For Prof Ratti, a communal way of life is not just more sustainable but more sociable. "If you live in a big city, you have access to lots of like-minded people, but in smaller communities you may only have a few thousand," he says.

"So why not create a like-minded community where it is easy to connect with people and sharing is the glue?"

His ideas were recently presented at German design exhibition Internationale Bauassstellung. IBA, the group that will ultimately decide what happens on the site, also heard proposals from other groups, including a car-sharing service to connect the site to Heidelberg using self-driving shuttles.

"It's about a process of transformation that we want to trigger," says Prof Kees Christiaanse, who works on the project. "Today, we are experiencing an atomisation of economic activity in ever smaller units that work complementary to large global firms. "Increasingly, we are depending on highly specialised small-scale enterprises.

"Carlo proposes a kind of infrastructure for these cross-fertilisations to take place, which will be of great value for developing the site."

Living and working space will also be communal, (c) Carlo Ratti Associati

Whether the project can create a truly sharing community remains to be seen, but marketing expert Prof Russell Belk thinks it is important to work out why people want to share in the first place.

"A sharing economy is more about short-term rental, via services like Uber, Airbnb or Zipcar," he says. "True sharing is more like what happens within the family and in some non-profit communal sites like CouchSurfing and Majorna [a volunteer car-sharing service in Gothenburg]."

"Part of the difference is whether there is a sense of community and caring rather than simply convenience. "The commune sounds to be somewhere in-between". "Most sharing ventures are not long-term operations unless they have economic as well as social incentives."

Whether the project can create a truly sharing community remains to be seen, but marketing expert Prof Russell Belk thinks it is important to work out why people want to share in the first place.

"A sharing economy is more about short-term rental, via services like Uber, Airbnb or Zipcar," he says. "True sharing is more like what happens within the family and in some non-profit communal sites like CouchSurfing and Majorna [a volunteer car-sharing service in Gothenburg]."

"Part of the difference is whether there is a sense of community and caring rather than simply convenience. "The commune sounds to be somewhere in-between". "Most sharing ventures are not long-term operations unless they have economic as well as social incentives."

Experimental living around the world

The Farm: founded in Lewis County, Tennessee, by 300 "flower children" from San Francisco, this commune is now America's oldest. Still home to about 200 people, it maintains its original values of non-violence and respect for the environment.

Christiania: probably Europe's most famous, this commune is a neighbourhood of about 850 residents in the Danish capital, Copenhagen. Temporarily abandoned in 2011, it is now open again. It has been a source of controversy for the Danish government since it opened in 1971, largely because of its cannabis trade.

Arcosanti: this experimental town was built in the 1970s in an attempt to fuse architecture and ecology. All the buildings are designed to work in harmony with their environment, many reflect the changing seasons so a maximum amount of sunlight penetrates during the winter and very little during the hot summer. Many also make use of solar power for heating, cooling and electricity.

Auroville: this city in southern India set up in the late 1960s to work towards "human unity" and the "transformation of consciousness". Seen by many as a microcosm of experimental world peace, its 2,000 residents come from 40 different nations.

Findhorn eco-village: set up in the 1960s, this village in Scotland decided in the 80s to concentrate on being an environmentally friendly community and now claims to have the smallest environmental footprint of any town in the modern world. Buildings are made from found materials - such as whisky barrels - and the village is powered by a wind turbine and a water treatment plant that makes use of algae, snails and plant life to purify the community's water supply.